Few of us make decisions based on a purely rational assessment of our own self-interest. And thank goodness for that! Life with homo economicus, “economic man,” would be dreary indeed. There is a deep tradition in economics that considers the role that “institutions”—defined here as traditions, cultural mores and social organizations—play in society. A cultural value of honesty, for example, contributes to a more efficient economy. Traditions and cultural norms, even without any claim to morality, also bring societal benefit. Laws and explicit rules cannot create a good society unless they are built upon a strong cultural foundation. I illustrate this below in three spheres: the macroeconomy, government, and the firm.

Few of us make decisions based on a purely rational assessment of our own self-interest. And thank goodness for that! Life with homo economicus, “economic man,” would be dreary indeed. There is a deep tradition in economics that considers the role that “institutions”—defined here as traditions, cultural mores and social organizations—play in society. A cultural value of honesty, for example, contributes to a more efficient economy. Traditions and cultural norms, even without any claim to morality, also bring societal benefit. Laws and explicit rules cannot create a good society unless they are built upon a strong cultural foundation. I illustrate this below in three spheres: the macroeconomy, government, and the firm.

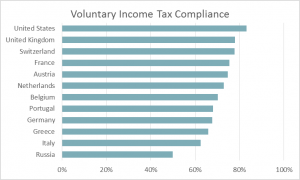

Consider national tax compliance. Americans cheat on their taxes less than citizens of other nations, much less in some instances. The Internal Revenue Service estimates that 83% of taxes owed were paid—and paid on time—in 2012. Contrast that record with Greece, where tax evasion has been called the national pastime: On average, the Greeks pay only 2/3 of what they should. And it isn’t because we hire more tax police. Greece spends four times as much per capita chasing tax cheats. Historically, the Russians have been even worse: Income tax compliance has been at 50%. Without a strong tradition of voluntary compliance, the central government spends more on enforcement and must rely on forms of taxation that are more easily enforced but may be less equitable and, in economic terms, create more inefficiency.

Consider national tax compliance. Americans cheat on their taxes less than citizens of other nations, much less in some instances. The Internal Revenue Service estimates that 83% of taxes owed were paid—and paid on time—in 2012. Contrast that record with Greece, where tax evasion has been called the national pastime: On average, the Greeks pay only 2/3 of what they should. And it isn’t because we hire more tax police. Greece spends four times as much per capita chasing tax cheats. Historically, the Russians have been even worse: Income tax compliance has been at 50%. Without a strong tradition of voluntary compliance, the central government spends more on enforcement and must rely on forms of taxation that are more easily enforced but may be less equitable and, in economic terms, create more inefficiency.

“What about ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ and the self-dealing that contributed to the financial crisis?” I’m not making a global claim to the moral superiority of the average American. Special interests have successfully lobbied for the insertion of custom tax provisions that make evasion, for some, entirely legal. Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index places the United States at #19 of 177 countries—not terrible, but not at the top with the Scandinavians and New Zealand. We have a strong compliance culture around taxes, but fall short in countless other spheres.

Culture and tradition also play an important role in the political sphere. This week the Supreme Court heard arguments in National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning. This is part of the long running Washington soap opera about presidential appointments—the Senate has been very slow to consider appointments from the Obama White House, fearful of Republican filibuster. Exasperated, the President made a few “recess” appointments—which persist until the next session of Congress—when the Senate was out of town, asserting that the Senate was not simply absent, but in recess. As the Senate was convening pro forma sessions every three days (presumably at the direction of the Majority Leader, Democrat Harry Reid), the Senate argues that it was not in recess. The appointments were therefore unconstitutional.

And we also witnessed the demise of the Senate’s longstanding filibuster rule. Silly rule, really: A senator could delay proceedings as long as he or she could keep talking. As senators are anything if not long winded, talking ad nauseum comes naturally. Only a vote of three fifths of the Senate could shut up the speaker. The minority party needs only 41 seats to threaten the majority with a costly and embarrassing filibuster. So Harry Reid and the Democrats called it off and changed the rule.

Culture and tradition matter. The Senate’s responsibility to consider presidential appointments in a timely fashion—and typically confirm the nominees—reflects deference to the Office of President, regardless of party. The Senate can and should refuse to confirm some appointments, thus nudging the President toward whatever consensus rules in that chamber. But generally the Senate plays nice and the President, for his part, doesn’t abuse the power to make recess appointments, even when the fact of the recess is unambiguous. Deference to tradition would make it unnecessary to rigidly define “recess” or remove the President’s power to act when a recess occurs.

The same principle applies to the filibuster. It may seem to be a silly tradition, but it served as an escape valve when a member of the Senate felt deeply and wanted to make a dramatic statement. The chamber would be nearly empty—the senator was welcome to talk, but other senators didn’t have to listen. And eventually the drama would end and business would resume. Using the filibuster (or threat of one) as a standard operating procedure, however, violated the cultural norm. Deference to tradition allows this “escape valve” to remain in place, a subtle component of the balance of power among the members and between the political parties.

Culture plays a role in the workplace, too. When I arrived at CGR after having been a SUNY college faculty member, I asked about the travel policy. “Be reasonable,” I was told. Reasonable??!! Where’s the list of allowable lodging expense by city? What’s the maximum reimbursement for dinner? A glass of wine is on your own tab, right?

At CGR, we pride ourselves on having fewer rules than large organizations—because we have a culture that respects our mission and engenders mutual respect among the staff. On the rare occasion that this trust is abused, it is apparent to all—and this reinforces the value we all receive from working in an atmosphere of trust and respect.

Culture is the foundation of a good society—and, surprisingly, a competitive economy. We can’t pass enough laws or hire enough cops to overcome consistently self-interested behavior. Preserving a moral code is the job of families, schools, the faith community—even the workplace. A market-based economy can harness our competitive and selfish reflexes to better ends: Markets, like laws, can help protect the community from individual greed. Yet economies can’t survive without a culture that reinforces trust and honorable behavior. No society prospers on self-interest that is limited only by markets or the rule of law.