Last week we looked at how the Affordable Care Act and the Republican replacement plan changed health insurance for those of us who buy insurance either through our employers or on the individual market. This week we’ll look at how the ACA and the new plan change access to health insurance for people with low income.

Last week we looked at how the Affordable Care Act and the Republican replacement plan changed health insurance for those of us who buy insurance either through our employers or on the individual market. This week we’ll look at how the ACA and the new plan change access to health insurance for people with low income.

Medicaid expanded under ACA

The ACA expanded Medicaid in two ways. First, it added adults in poverty to the program, not just poor children and their parents. Before the ACA, low-income adults without dependent children were ineligible for Medicaid in 26 states—the cost of doctor visits, hospital stays, prescription drugs—all had to be paid in cash. The ACA also pushed Medicaid eligibility up to 138% of the federal poverty line (FPL) for everyone (although some states, like New York and California, were already there). For context, the FPL for a single adult is $12,060 and, for a family of 3, $20,420.

At least until a group of states took the matter to the Supreme Court, which ruled that Congress could not require the Medicaid expansion, even though most of the cost was shared among all federal taxpayers. Currently, 19 states have chosen not to expand Medicaid eligibility.

Marketplace subsidies

The near-poor also get a break under the ACA—for those earning between 138% and 400% of the federal poverty line, generous tax credits significantly reduce the cost of coverage, particularly at the low end of the income scale. If your income is 150% of the FPL, the subsidy keeps your marketplace premium to 4.1% of your income. At the top of the scale (for subsidized coverage), the subsidy caps the cost of coverage at 9.7% of income.

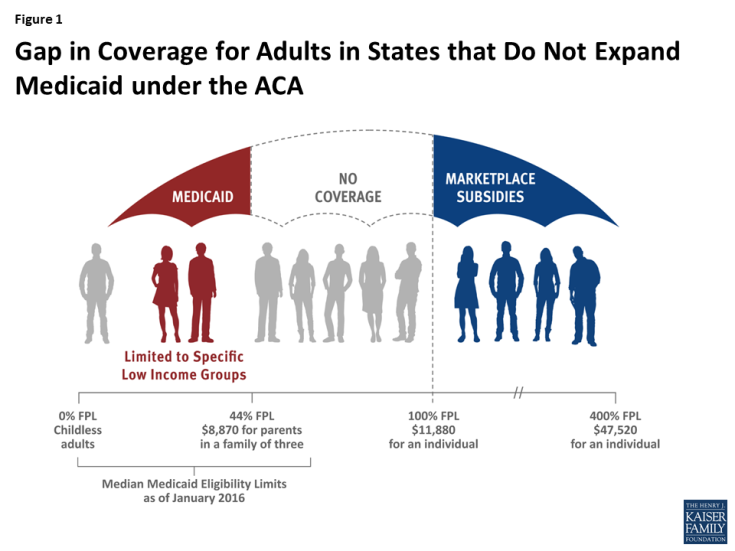

The coverage gap

Remember the 19 states that didn’t expand Medicaid? The insurance subsidies only apply to individuals above the federal poverty line (FPL). Thus single adults earning $12,060 in Texas or North Carolina or Florida, etc. can get health insurance for 2% of income—about $242. If their income falls by a dollar to $12,059, they lose all coverage. The ACA’s subsidies for the near poor, combined with the decision to reject the Medicaid expansion, created a tremendous inequity between those just above and those below the FPL. At the same time, mixed acceptance of the expansion opened up a yawning chasm in health care coverage between these 19 states and the rest of the country.

What’s in store for people with low incomes?

The plan that passed the House of Representatives swaps the marketplace subsidies for the tax credits mentioned last week. A 27 year old with income of $20,000 now receives an average subsidy of $3,225 under ACA; under the new plan, the tax credit would be $2,000 instead. The change is reversed at the other end of the age spectrum. Higher income people in my 60-something age bracket get no outright subsidy under ACA but would receive a $4,000 tax credit under the new plan. That said, 60-somethings can be charged five times as much under the new plan v. three under the ACA. Talk about complicated! See Kaiser Family Foundation’s interactive map here. Still, it’s clear that “young and poor” do better under ACA while older people who are better off are favored under the Republican plan. The middle is a jumble.

The most significant change, mentioned in the last installment, may be the states’ ability to “opt out” of many of the ACA’s coverage rules. This will affect more than just people living in the states that opt out as multi-state employers can adopt the rules of any state in which they have employees.

The Medicaid expansion on life support

Given the number of red states that chose to expand Medicaid coverage (including Indiana, home of VP Pence), simply pulling the plug on the expansion is politically impossible. No politician wants to risk taking health insurance away from someone who just got it. The House bill freezes the expansion and changes funding in a way intended to shrink spending over time.

Summing up

The Affordable Care Act was a revolution in burden sharing for health care services. Premiums for many went up to pay for coverage for individuals previously without insurance, some because of illness and others because of income. New taxes were established and old taxes increased to pay for health insurance subsidies that hadn’t existed before. The out-of-pocket annual maximum and the end of lifetime maximums will save many families from medical bankruptcy. Coverage for preventive services may save lives and, perhaps, moderate the increase in health insurance cost.

But insurance companies couldn’t afford to offer ACA plans without getting more cash from participants. Higher premiums were part of the solution, but so was a dramatic expansion in the use of high deductibles. While already part of the insurance scene before the ACA, they’ve become ubiquitous since. And ACA is in trouble in many individual markets—with the Administration failing to enforce ACA regulations, many of the gains achieved in the ACA will disappear.

And the House-passed GOP plan? The Congressional Budget Office predicts that 23 million will lose Medicaid benefits, 14 million in the first year alone. Subsidies for the near-poor will disappear. People with costly conditions may find rates rise exponentially in states that “opt-out” of the ACA’s regulations. At the same time, taxpayers will see a number of new taxes will go away and others fall.

The initiative for ACA changes has passed to the Senate. What emerges matters to all of us—for some, self-interest will be the guiding principle. For many of us, however, Jesus’s call to put others’ needs ahead of our own will influence our voices and our votes.