Summer’s finally here, but just weeks ago students in schools across New York completed state tests that carry bigger stakes than ever before. This is the first year that test scores will feed into teacher evaluations, and with the tests now aligned with the new Common Core curriculum, many observers believe passing rates will decline.

Summer’s finally here, but just weeks ago students in schools across New York completed state tests that carry bigger stakes than ever before. This is the first year that test scores will feed into teacher evaluations, and with the tests now aligned with the new Common Core curriculum, many observers believe passing rates will decline.

The push-back against testing and increased accountability has grown, and it’s easy to see why. Students, families and schools have seen passing rates decline, felt more pressure to increase performance and wondered whether testing now gets too big a space in education. It’s worth revisiting why and how these changes came about, and examining the long-term trend in performance.

As recently as 20 years ago, New York had very little in the way of rigorous testing or accountability for schools. Students in 3rd and 6th grade took relatively simple tests in core subjects, and high school students went into 1 of 2 tracks: Regents exams and diplomas, or very rudimentary Regents Competency Tests and local diplomas.

In the mid-1990s, New York implemented more rigorous tests in 4th and 8th grades and began phasing out the competency tests and requiring all students to pass Regents exams. The state also began publishing School Report Cards listing test results and other data on every school. Under President Bush, the accountability movement went national, as the No Child Left Behind Act required testing in 3rd through 8th grades and mandated that schools report not just aggregate performance but also student performance based on economic status, race and ethnicity, disability, and English language learner status.

These developments, which exposed painful realities about achievement gaps among different groups of students, were important. By making data on performance of all groups by school visibly public, they supported the notion that offering poor and minority students a sub-standard education was unacceptable. Under New York’s accountability system, schools are required to make progress on test results with all groups of students, which has led to citations and school closures, the merits of which can be debated. Over the last several years, the state has worked to increase the rigor of the tests and required students to answer more questions correctly in order to pass. And the push for accountability has now made its way directly to teachers, who will be evaluated this year in part on how much growth they attain on student assessments.

Whether we’ve gone too far with testing and accountability is not a question that can be answered here. What is clear from the data is that many groups that historically have had lower school achievement – in particular low-income, African American and Hispanic students – continue to struggle to meet ever-increasing standards.

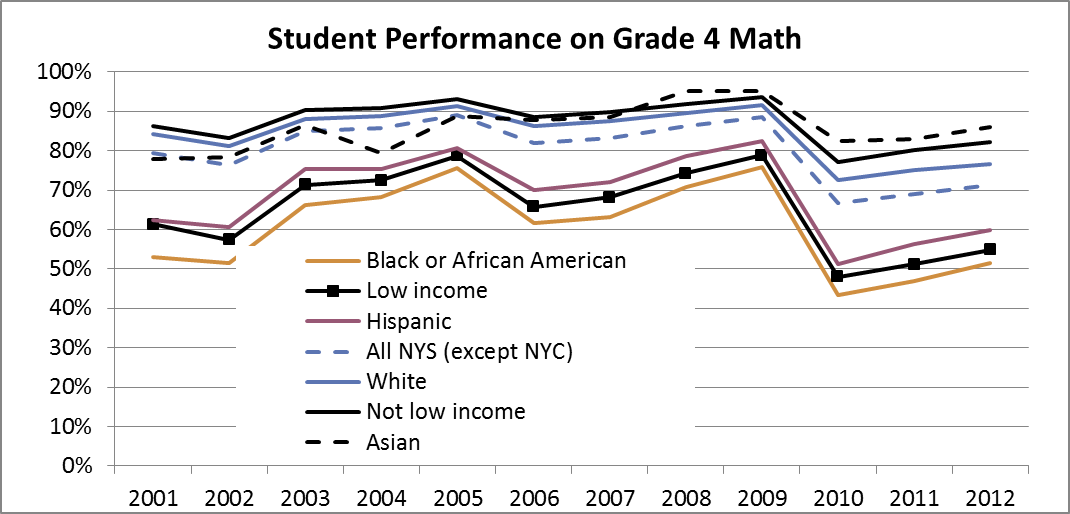

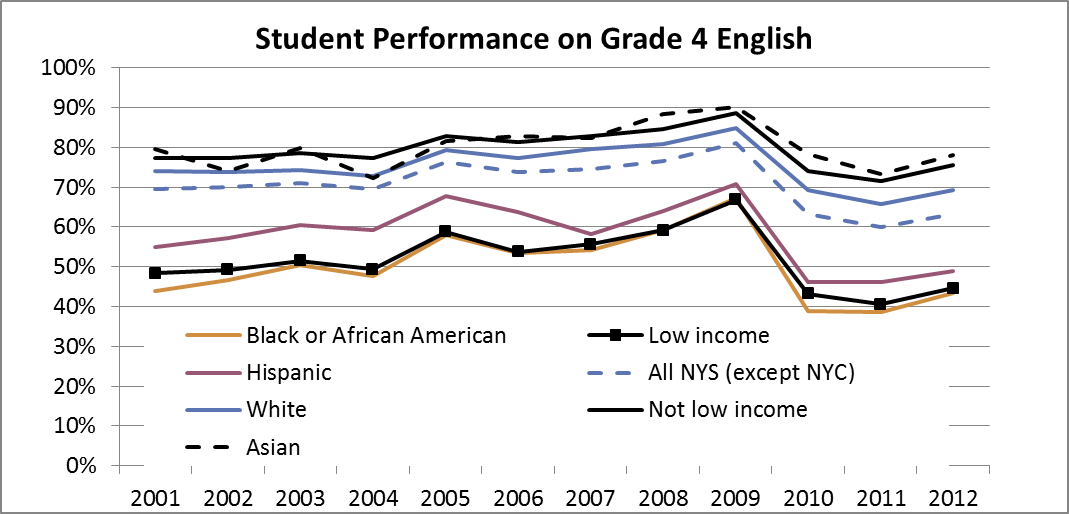

Take the examples of the state’s 4th grade math and English exams, which were revised in 2010 along with the rest of the elementary and middle school testing battery. After New York State’s research indicated the tests were not accurately assessing skills, the passing thresholds were increased so that students had to complete more of the test correctly in order to pass.

As the chart below shows, passing rates in 4th grade math were lower among low income, African American and Hispanic students (the bottom 3 lines) even before the revisions in 2010. In 2010, passing rates for those 3 groups plummeted more than 30 points, while other groups experienced less dramatic declines. Since then, gains among those 3 groups have been higher than the rest of the population, but the achievement gap remains.

The results for English are similar – declines in 2010 of more than 20 points among the 3 lowest performing groups but less subsequent improvement, though the passing rate for African American students did rise 5 points by 2012.

With this year’s Common Core-aligned tests, it remains to be seen whether overall pass rates will fall and whether rates for historically disadvantaged groups will fall further. Like the efforts to raise standards that preceeded it, the Common Core promises to level the playing field by delivering rigorous content and instruction to all students. It will take skilled teachers and well-managed districts to implement these changes in ways that enhance, rather than detract from the educational experience of children. And it will take time and support from the community outside school. The end goal is not just to raise the academic bar, but also to get more children over it.