Part 1: Health Insurance Coverage for the Poor

The Affordable Care Act’s initial enrollment period is over and Health & Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sibelius has resigned, having earned a jacket full of Purple Hearts from countless Congressional hearings. What have we wrought?

Make no mistake—this will revolutionize health care delivery in the United States. As the Arab Spring suggests, revolutions can be good or bad. Or both, as in this case.

In the first of a two-part column on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), let’s focus on how coverage for the poor has changed.

Who’s Covered?

As the states have long been obligated to pay a portion of the cost of Medicaid, they have retained a high level of autonomy over the program—both coverage and eligibility. As a result, Medicaid has been a patchwork of 51 different programs governed under an array of federal laws and waivers.

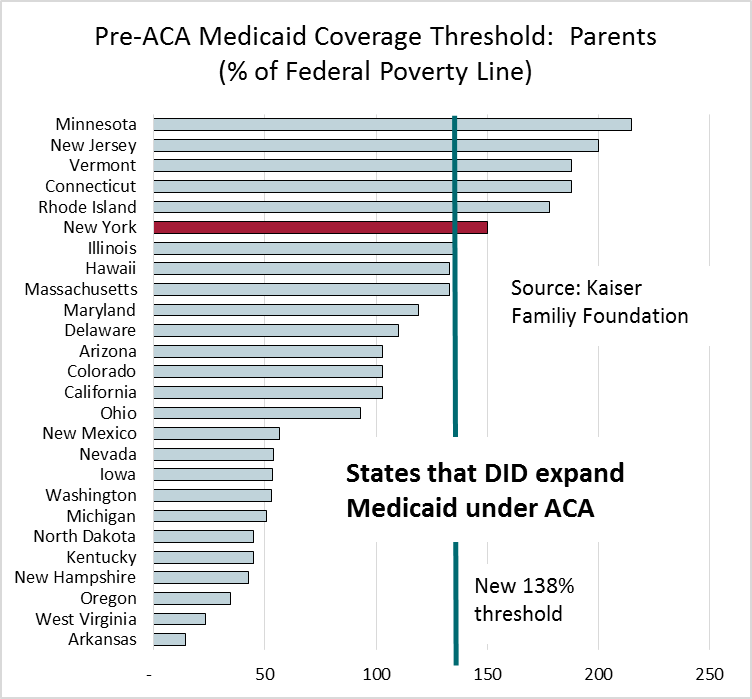

ACA included two revolutionary changes in Medicaid coverage. First, the program was expanded to cover nondisabled, childless adults with the income threshold set to 138% of the federal poverty line (FPL). Prior to ACA, only 8 states (including New York) provided coverage to this population (through federal waivers). Second, ACA increased the coverage threshold for parents, again to 138% of the FPL. [Note: Technically, the line is 133% but the law permits 5% of income to be “disregarded,” thus 138% is the practical boundary.]

These expansions in eligibility were mandatory and would have imposed some consistency on the state programs. In exchange, Congress promised that federal taxpayers would pay most of the cost of the expansion—the full cost for 3 years and 90% thereafter.

This eligibility provision was struck down by the Supreme Court. While the plaintiffs sought to have the entire law thrown out, the Supremes split the baby in true Solomonic fashion and the Medicaid expansion became optional for the states.

The law was aimed at improving access to health care for a)individuals and families at or near the poverty line and b)individuals and families who are working but lack access to an affordable plan. The Medicaid expansion was designed to fix the first problem. The Health Insurance Marketplace, offering subsidized coverage between 100% and 400% of the FPL, was designed to fix the other. When the Medicaid expansion became optional, it opened up a gap in coverage.

The Coverage Gap

Pennsylvania is one of 22 states that chose not to expand Medicaid coverage. Suppose you live in Pittsburgh. You’re a nondisabled, childless adult and you earned $11,490 in 2013, right at the federal poverty line. You are eligible (obligated under the law, actually) to buy health insurance. ACA guarantees you access to a “silver” plan for a cost of no more than 2% of your income. If you buy one of the “silver” plans available in Pittsburgh, you pay only $230. You could spend more and buy a “gold” or “platinum” plan or you could enroll in a “bronze” plan and pay nothing.

Ah, but what if you lost your job late in the year and you earned only $11,480? Then you’re out of luck. Pennsylvania Medicaid provides no coverage for nondisabled, childless adults. And you don’t earn enough to qualify for marketplace coverage.

This “coverage gap”—where individuals with income at or above the federal poverty line are eligible for subsidized market place coverage but poorer individuals are not—affects an estimated 4.8 million people (in AL, AK, FL, GA, ID, IN, KS, LA, ME, MS, MO, MT, NB, NC, OK, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, and WY). See map here.

This may be the first time in history that some Americans will have an incentive to overstate their income to the Internal Revenue Service. Will the IRS audit the tax returns of individuals who claim marketplace credits with inflated income?

States that Took the Deal

The coverage gap doesn’t apply here in New York, as we have been covering nondisabled, childless adults up to 100% of the FPL. Federal subsidies are funding the cost of expanding to 138% of the FPL. In addition to New York, seven states offered coverage to this population before ACA passed. Under ACA, 20 states have begun to offer Medicaid coverage to nondisabled, childless adults this year.

What about nondisabled parents? Prior to ACA, all states provided coverage to nondisabled parents, although often at a low income threshold. New York covered nondisabled parents up to 150% of the FPL before ACA, then reduced the threshold to 138% when the Marketplace was established.

FYI, 138% of the FPL in 2014 is $16,105 for a single and $27,310 for a family of 3.

Enrollment Strong

Despite the desperate hopes of the naysayers, the final enrollment in either marketplace plans or expanded Medicaid plans is about 8.0 million: Through February, marketplace enrollment (not Medicaid) was 4.2 million. Medicaid enrollment was another 3 million. Last week the White House announced the total, but the detail will be forthcoming (White House update here). See comment from longtime health policy guru Gail Wilensky on what we still hope to learn about enrollment.

Despite the desperate hopes of the naysayers, the final enrollment in either marketplace plans or expanded Medicaid plans is about 8.0 million: Through February, marketplace enrollment (not Medicaid) was 4.2 million. Medicaid enrollment was another 3 million. Last week the White House announced the total, but the detail will be forthcoming (White House update here). See comment from longtime health policy guru Gail Wilensky on what we still hope to learn about enrollment.

And why not? Despite some bizarre advertising from opponents, the Affordable Care Act is a good deal for individuals. Of the 4.2 million who signed up for Marketplace plans, 83% expect to receive a federal subsidy. The existence of the Marketplace (both federal and state-based) has spurred Medicaid enrollment, too.

Are we reducing the number uninsured? A survey concluded on March 28 by the RAND Corporation reports that about one-third of individuals signing up for new plans were previously uninsured, slightly higher than that reported by a survey conducted during February by McKinsey. The remainder signed up for a Marketplace plan as a replacement for prior coverage. The Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center also conducted a survey in February and estimates that the share of individuals without coverage has fallen from 17.5% to 15.2%. The decline is more pronounced in states expanding Medicaid, as we would expect, from 15.4% to 12.4%.

What about Cost?

Medicaid is entirely funded by the federal and state taxpayers. A substantial increase in total Medicaid enrollment doesn’t come cheap. Most Marketplace enrollees are receiving subsidies and these, too, will add up. Although the Congressional Budget Office just announced that their models are predicting lower total cost than they did previously, prediction is tough when many things change at once.

In the next installment, we’ll explore more questions:

- Might cost be driven down by other ACA changes, such as the broad shift to high deductible health plans?

- What happens to primary care access when we increase the number of people covered by health insurance?

- What are the implications of the coverage gap and other ACA provisions on labor mobility?

- Is the Affordable Care Act a “Trojan horse” for a single payer health system?