Will more be insured? Will we have the health professionals to meet their needs?

Last month’s column looked at how health insurance eligibility changed under ACA and explored the “coverage gap” in states choosing not to expand Medicaid. This week we’ll explore other implications of this revolutionary change in how health insurance is secured and paid for.

On balance, will the share uninsured go down?

Cutting the ranks of the uninsured is a key objective of ACA. Not all of the 8 million who signed up for new plans were previously uninsured: According to early surveys, two thirds to three quarters of these enrollees were changing plans. No surprise here. ACA offers subsidies that are significant for many, making the Marketplace plans very attractive for those who qualify. Others who didn’t qualify for subsidies still found the Marketplace plans a good deal. Competition spurred by the Marketplace drove down prices for nonemployer plans in some states, including New York.

Yet some will choose to pay the penalty for being uninsured instead of the premiums. Insurers are now required to cover a fixed set of preventative services at no extra cost to the consumer. The law also limits what consumers can be charged for care within a single year. Initially, ACA required that a 2014 policy must cover all costs above $6,350 for singles or $12,700 for families. That’s the “out-of-pocket maximum,” now delayed until 2015. (These deductibles are subsidized for individuals and families below 250% of the poverty line.) This shifts the financial burden of major illness from the insured to the insurer. Both changes make for better insurance—but they cost insurers more and premiums will rise.

Premiums will change in future years, too, thus the balance of that “buy insurance or pay the fine” calculus. Actuaries, the beleaguered insurance staffers who have the job of estimating cost were “flying blind” in this first year. Normally, insurers can assume that the health status and behavior of the insured will be much the same as before. With so much changing at once in 2014, the task of setting rates was perilous. Some set rates too low and must raise them for 2015. Others may have set rates too high, lost customers, and will cut rates next year.

In summary, while rates of insurance among those who qualify for subsidies should rise, ACA’s critics warn that higher overall policy costs may actually cut coverage rates for others. While this seems unlikely, it is possible. And the “coverage gap” in some states remains (see last column). Stay tuned.

Can the health care system absorb new enrollees?

Increasing insurance coverage is only one step. Can our healthcare system serve all of these new patients?

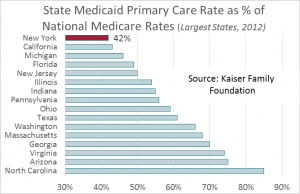

Medicaid enrollees already have a hard time finding physicians willing to accept the rates offered, particularly in New York where primary care reimbursement under Medicaid, when compared to Medicare rates (which are the same nationwide) is second lowest in the nation (after Rhode Island). That’s why health care delivery under Medicaid in New York is so dependent on Federally Qualified Health Centers like Rochester’s Jordan Health Center. These clinics are better funded under Medicaid than are physicians in private practice.

When ACA is fully in force, primary care docs could be in short supply across the board. The Association of American Medical Colleges estimates that the nation will face a shortage of 130,000 physicians by 2025. Inevitably, a larger share of primary care will be performed by other health professionals, particularly nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

When ACA is fully in force, primary care docs could be in short supply across the board. The Association of American Medical Colleges estimates that the nation will face a shortage of 130,000 physicians by 2025. Inevitably, a larger share of primary care will be performed by other health professionals, particularly nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

New York just made this easier by passing the Nurse Practitioners Modernization Act. Effective next January, NPs will no longer be required to have a formal collaboration agreement with a physician. Particularly in rural areas, it has been difficult for some NPs to find a physician willing to collaborate. Statewide, most NPs will probably continue to be part of a physician-led practice, but the law opens new possibilities.

Greater reliance on midlevel health practitioners can help address the shortage. The RAND Corporation estimates that nurse-managed health centers can help fill the gap. Research indicates that NPs and PAs provide excellent primary care. Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland performed a meta-analysis of 37 studies comparing care from NPs and physicians. They concluded that rates of hospitalization, mortality, patient satisfaction and several other specific measures were equivalent across NPs and docs.

Primary care is also going retail. Downstaters now have access to a network called “CityMD,” staffed by emergency medicine docs. Look ‘em up on Yelp: The clinic in the Flatiron District earned 4.5 stars from 132 reviewers. (Now that’s retail.)

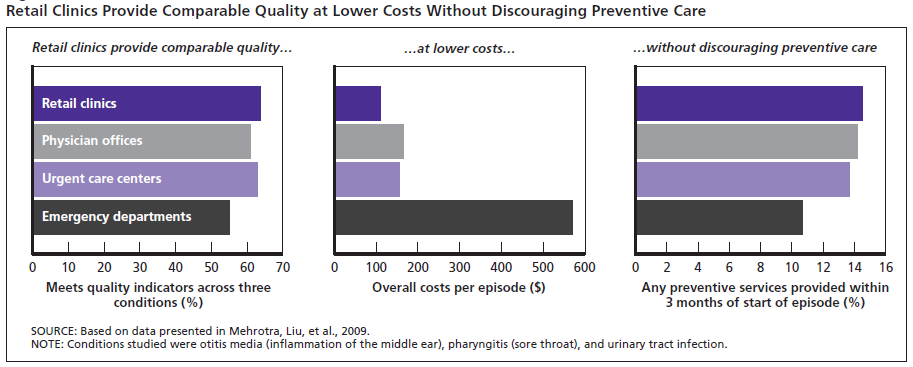

Retail clinics score well on quality measures, too. In its monograph, Health Care on Aisle 7, RAND applied 12 quality-of-care measures to retail clinics, physician offices, urgent care centers, and hospital emergency departments. The first three were found to be equivalent in quality—the lowest quality care was received in the ED.

Can we accommodate the newly insured? Probably, but not without changing primary care service delivery. Look for more states to expand the role of midlevel professionals.

Cost control?

Finally, what’s the likely impact of ACA on cost? Putting aside formal cost control efforts like payment reform and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for another column, ACA’s big impact on cost may come from rise of high deductible plans. Between out-of-pocket-maximum and required preventative care services, insurers have dramatically expanded the share of plans with substantial deductibles.

High deductibles do change behavior and will cut spending: Last July the Employee Benefit Research Institute reported the results of a five-year trial with high deductible plans: Spending in the first year fell by 25%. (Yes, we worry about the impact on health outcomes: It is hard to discourage unnecessary care without also discouraging needed treatment. But that, too, is another column.) While more high deductible plans may be an unintended consequence of the Affordable Care Act, they could have a larger impact on cost than any of the planned cost control measures.

Update on Medicaid Enrollment Post-ACA

Keeping score for the ACA’s impact on enrollment is complicated by the fact that the Marketplace spurred Medicaid enrollment among people who were previously eligible, even in states that didn’t expand Medicaid coverage. A June 4 release from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reports that the Medicaid rolls grew by 6 million between the July-September 2013 average and April 2014. That’s a 10% increase across all states. Among states that did expand Medicaid, the average increase was 15% while the increase was about 3% for states that didn’t expand coverage.

Figures varied widely, however. New York is technically in the “expansion” group but its pre-ACA eligibility rules were not very different from eligibility under ACA—enrollment in our state grew 6%. Nine of the expansion states, by contrast, saw enrollment grow by 25% or more—49% in Oregon and 43% in Nevada. If our goal is to reduce the share of individuals without health insurance, it doesn’t matter if they were eligible before or not.