Governor Cuomo’s push for an increase in the minimum wage has a worthy goal—providing workers with enough income to support their families. That’s a goal most of us support.

Governor Cuomo’s push for an increase in the minimum wage has a worthy goal—providing workers with enough income to support their families. That’s a goal most of us support.

Yet as an anti-poverty strategy, a $15 minimum wage has a number of flaws, the sum of which are fatal. First, it is a shotgun blast that helps ALL low wage workers, not just breadwinners of families in poverty. We’re effectively increasing the sales tax on consumers (as prices will rise) and taxes on business (as profits will fall) and distributing the benefit to the teenage children of the middle class as well as people in poverty. Second, it eliminates jobs for the most vulnerable. Those who are the most in need are often the least skilled, thus are the workers who will get passed over for jobs at the higher wage. The risk is greatest in sectors where technology is displacing labor—fast food comes to mind. The impact on employment is most assuredly negative, although we can debate the magnitude. These points (and others) have been made in this space before.

A third problem has received little attention. Increasing wages will reduce a family’s eligibility for many forms of social assistance, which is a good thing, on its face. But there are practical consequences that have the effect of discouraging work. Social assistance phases out as income rises; declining benefits acts much like a tax on added earnings. Assuming a standard 2,080 hour work year, a $6 increase in the hourly wage will increase annual income by $12,480. Now with income of $31,200, a single parent with two children will lose benefits received at a $9 wage. If the family is receiving a Section 8 housing voucher (not all who qualify for Section 8 get vouchers), it faces a 53% “tax rate.” The family gets to keep less than $6,000 of added earnings.

Yes, that’s still a big improvement for this family. But others in poverty will lose jobs and most will pay higher prices. There is a better, more targeted, way to help. The federal and state Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) are the largest anti-poverty programs for families with children, and enjoy strong bipartisan support from both major political parties. The EITC, unlike other means-tested anti-poverty programs, is designed with the working poor in mind, and encourages more work and higher earnings. The credit equals a percentage of earnings until a credit reaches a maximum, and then gradually phases out as earnings continue to rise. As an increase in the EITC is not considered income for the purpose of determining eligibility for other programs, the money goes directly to improving their quality of life.

Unlike an increase in the minimum wage, the EITC doesn’t reduce hiring or prompt layoffs. Instead, the EITC provides crucial financial support to low-income households and encourages work. Studies show that by increasing the value of low-wage work, the EITC generates higher workforce participation and removes people from the public assistance rolls.

In the City of Rochester alone, over 27,000 tax filers received more than $69 million in federal EITC tax refunds in 2013, with nearly 98% of funds going to tax filers with children. New York State matches 30% of the federal EITC, so the average Rochester family with children that received an EITC payment in 2013 gained roughly $4,000 in state and federal refunds from program. Along with food stamps, the state and federal EITC programs are the most widely-used form of government support for low-income families in this community.

But there’s a problem. Families receive the entire amount at tax time as a lump sum. Families living paycheck to paycheck find financial planning difficult in the best of times. The fact that the money comes all at once doesn’t make this easier. Many families incur substantial household debt in anticipation of receiving the EITC refund—unscrupulous lenders and vendors may be partly to blame.

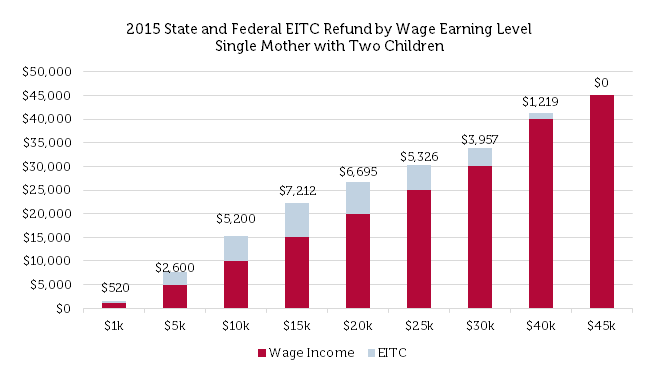

For many low-income families, the EITC plus other tax credits make up a large portion of their annual income. For example, a single mother with two children who makes $15,000 per year would receive over $7,200 from the state and federal EITC, nearly half her annual wage earnings.

Although this problem is widely known and often discussed, where’s the legislation to fix it? Expanding the EITC and converting it to a monthly payment would achieve the goals sought by proponents of a $15 minimum wage – improving the lives of many low-income New Yorkers – but would avoid distorting labor markets and cutting jobs for the most in need. We urge the Governor and legislative leaders to craft and pass legislation supporting an expansion of New York’s contribution to the EITC and making the payments monthly. Moreover, we urge them to work with our two senators and members of Congress to push these sensible reforms nationally.

Expanding the EITC is politically difficult as it would require an explicit tax increase. Far better, however, that we increase taxes openly to support a program that targets families in need. An increase in the minimum wage has the effect of a tax, yet its burden would fall on rich and poor consumers alike, not simply on the “fat cat” corporations that are the target of proponents’ speeches. Nor does the EITC make it even more difficult for lower skilled workers to get a toehold in the mainstream economy.