The Polar Vortex has me thinking about global warming. No, not the reflexive, “How could the world be warming and still post the coldest temps in recent memory?” I’m on board with the scientific consensus on climate change and I’ve a healthy appreciation for the randomness of complex systems. Most economist & weather forecaster jokes are interchangeable, after all.

The Polar Vortex has me thinking about global warming. No, not the reflexive, “How could the world be warming and still post the coldest temps in recent memory?” I’m on board with the scientific consensus on climate change and I’ve a healthy appreciation for the randomness of complex systems. Most economist & weather forecaster jokes are interchangeable, after all.

The message of this frigid winter is that climate change is massively disruptive. We’ve watched (a bit smugly, perhaps?) as Atlanta and Birmingham struggled with what seemed a mere dusting of snow. More change means more disruption. What can be done? Political scientist David Victor, in his book Global Warming Gridlock, paints a complex and frankly bleak picture of the policy challenge posed by climate change. The Kyoto Summit and its sequel in Copenhagen have both failed to dent the problem.

The message of this frigid winter is that climate change is massively disruptive. We’ve watched (a bit smugly, perhaps?) as Atlanta and Birmingham struggled with what seemed a mere dusting of snow. More change means more disruption. What can be done? Political scientist David Victor, in his book Global Warming Gridlock, paints a complex and frankly bleak picture of the policy challenge posed by climate change. The Kyoto Summit and its sequel in Copenhagen have both failed to dent the problem.

Climate change is a public policy nightmare. First, the complex scientific models rely on a mountain of assumptions and data that don’t always agree—in Victor’s words, “The climate system is a coupling of chaotic and imperfectly understood systems.” Policy wonks ask the impossible of scientists: What concentration of CO2 will trigger what temperature change? When? What will warming mean for the climate? This tedious winter couldn’t have been predicted with confidence 6 months ago. We can’t expect precise weather outcomes decades hence from uncertain changes in CO2 concentrations. And the many assumptions and inconsistent data leave the warming consensus itself open to noisy debate.

Second, the benefits of carbon controls go to future populations, but the bill gets paid in the present. If intergenerational planning isn’t hard enough, the timing reinforces a division of the world community by income. Planning for the future is a privilege of the rich—the poor struggle to survive today and tomorrow.

Third, the impacts fall unequally on the world community. The Kyoto Treaty was negotiated in an island nation threatened by sea level rise with minimal domestic fossil fuel reserves. Of major nations, Japan has the most to gain and the least to lose from cutting emissions. Russia, by contrast, could do with a bit of warming and lives off the sale of its oil and gas reserves. A more navigable Northwest Passage (from melting Artic ice) is also good for Russia.

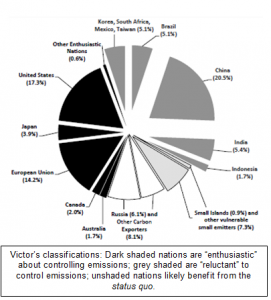

Finally, the “edge” of the problem is concentrated in a few emerging economies, whom Victor dubs “reluctant” participants in emission control. One-fifth of 2010 CO2 emissions came  from China, with India and Brazil contributing another tenth. The nations that are the most enthusiastic about controlling emissions—the European Union and Japan—were responsible for less than 20%, slightly more than the U.S.’s 17%. Yet nearly all growth in emissions will come from those reluctant nations. Offsetting their increases by reductions elsewhere would require implausibly draconian policy change.

from China, with India and Brazil contributing another tenth. The nations that are the most enthusiastic about controlling emissions—the European Union and Japan—were responsible for less than 20%, slightly more than the U.S.’s 17%. Yet nearly all growth in emissions will come from those reluctant nations. Offsetting their increases by reductions elsewhere would require implausibly draconian policy change.

The international treaty process can’t address this challenge. Kyoto Protocol signatories made visible progress in reducing emissions of gases that were cheaply controlled, but these have only a minimal impact on warming. Kyoto’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) channels rich country dollars into emission-reducing schemes in emerging economies but is believed to have been broadly “gamed” by recipient nations, who sought CDM cash for actions they would have taken on their own. See here.

What does Victor suggest? He begins by popping one of my cherished balloons. After demonstrating that a carbon tax is the most efficient and effective means of control (yes!), he notes that this imposes visible costs on well-organized interest groups—e.g. energy companies and energy-intensive businesses, like manufacturing. Good policy, dreadful politics. Instead of relying on efficient market forces, Victor believes that the only viable approach is old style “command and control” regulation that “channels benefits to well-organized groups and away from the pockets of the unsuspecting.” Mandated subsidies to new energy technology, paid by electric ratepayers, has this characteristic. The “systems benefit charge” in NYS is one example.

Victor suggests that “clubs” of interested nations hold more promise than UN-sponsored global summits—Japan and the EU could establish a verifiable CDM-like program with China, India and Brazil, for example. Given the challenge, however, he concludes that policy can only achieve so much. “It is much sexier to imagine bold schemes that stop global warming rather than the millions of initiatives that will be needed to cope with new climates. Yet the unsexy need to brace for change is unavoidable.” He admits that his research into new policy directions have led him “to a much darker place” than he began.

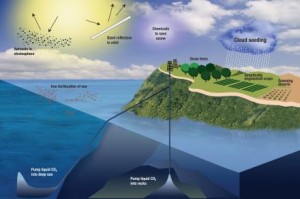

Unlikely to earn him the applause of the environmental community, he also urges “readying some emergency plans. Those will include intervening directly in the climate to offset of some of the effects of climate change, which is also known as ‘geoengineering.’” Scientists interested in such research point to the temporary cooling effect of volcanic eruptions. The release of airborne particulates into the upper atmosphere reduces heat gain and might be imitated to offset CO2 emissions.

Unlikely to earn him the applause of the environmental community, he also urges “readying some emergency plans. Those will include intervening directly in the climate to offset of some of the effects of climate change, which is also known as ‘geoengineering.’” Scientists interested in such research point to the temporary cooling effect of volcanic eruptions. The release of airborne particulates into the upper atmosphere reduces heat gain and might be imitated to offset CO2 emissions.

His bleak assessment of the policy context helps explain why climate change is so politically polarizing. Victor argues that “command and control” policies are our only option. As these dictate larger and more intrusive government, they rile small government activists. Those of us who are sensitive to the many failings of powerful central bureaucracies are eager to believe that the science is faulty. Doesn’t the Polar Vortex prove it? Chill on!