The French have voted with their hearts and picked Francois Hollande as President. And who can blame them for wanting to be more like Italy and less like Germany? More Roman Holiday and less The Spy Who Came In from the Cold?

The French have voted with their hearts and picked Francois Hollande as President. And who can blame them for wanting to be more like Italy and less like Germany? More Roman Holiday and less The Spy Who Came In from the Cold?

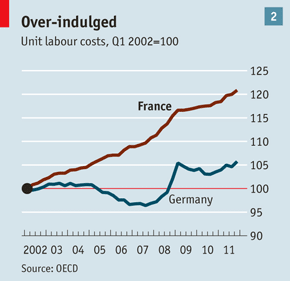

We should be grateful to the French. We need exemplars—countries whose policies we embrace and countries whose polices we avoid. France seems determined to set a bad example, if they expect Hollande to follow through on his promises. This is a nation that hasn’t run a budget surplus in 35 years, where labor costs have been rising in the face of blistering global competition, and where the public sector controls more than half of the economy. Hollande promises to hire more public sectors workers, raise the marginal tax rate to 75%, and reverse Nicholas Sarkozy’s feeble encroachment on the entitlement mindset of the French worker.

Sarkozy has changed the competitive landscape in France only slightly. And his successes were hard fought. In 2010, his proposal to raise the retirement age from 60 to 62 sparked widespread protests—his success then contributed to Sunday’s defeat. Francois Hollande has promised to roll back this change, despite the fact that life expectancy in France continues to rise. It was France’s last Socialist president, Francois Mitterand, who lowered the retirement age to 60 from 65 in 1982.

Sarkozy has changed the competitive landscape in France only slightly. And his successes were hard fought. In 2010, his proposal to raise the retirement age from 60 to 62 sparked widespread protests—his success then contributed to Sunday’s defeat. Francois Hollande has promised to roll back this change, despite the fact that life expectancy in France continues to rise. It was France’s last Socialist president, Francois Mitterand, who lowered the retirement age to 60 from 65 in 1982.

The world is a much more competitive place than it was in 1982. “Emerging Asia”—Asia less Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan—contributed about 9% of global GDP in 1982, rising to 19% in 2011. China’s share alone rose from under 3% to nearly 10%. Countries outside Asia have emerged as competitors, too. Brazil’s share of world output doubled to 3.5%. Many of the countries of Eastern Europe now compete in global markets. FYI, the U.S. share of global GDP fell from 30% in 1982 to 22% in 2011. And France’s share fell from 5.3% in 1982 to 4% in 2011.

Not only is France saddled with a sclerotic public sector and high labor costs, it may be failing to prepare a 21st century labor force. U.S. News and World Report ranked the world’s top universities in 2011: France held just two spots in the top 100: École Normale Supérieure and École Polytechnique, both in Paris, ranked #33 and #36, respectively. South Korea had three on the list, China five, Japan six and Australia eight. The U.S. boasted 31. At the K-12 level, France’s students perform in the middle of the pack. See PISA international student assessment for more.

Mitterand’s policies were more centrist than his rhetoric, of course, and Hollande may follow Mitterand’s example. His public pronouncements since the election suggest that he’s trying to walk back off the plank of his own campaign promises.

Hollande is likely to play a productive role in addressing Europe’s economic crisis. He will attempt to persuade Europe to soften the stern austerity imposed on its more profligate members—Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. A few months ago, Americans debated whether Congress should allow the payroll tax cut to expire. This would have driven up labor costs but reduced the budget deficit. While fiscally prudent, it would have imperiled the recovery. We chose not to take the gamble.

Europe faces a similar choice. The Great Recession put to the test the Euro’s dubious premise—that currency union can survive outside of political union. Europe’s creditors and debtors are in different countries: The “all for one and one for all” we struggle to maintain in the United States is far more difficult in the distinctly disunited states of Europe. Yes, if the Euro is to survive over the long term, the region’s spendthrifts must behave better. But the dose of cod liver oil administered by Merkel’s German government—with the full throated support of Sarkozy’s French one—is proving too much to swallow. Like our payroll tax reduction, the process of persuading Greece to act more like Bavaria will have to wait.

Sarkozy has been a quixotic leader, and stylistically at odds with France’s image of a president, more like a flamboyant American political figure than a reserved French one. Perhaps that explains why Americans seem to understand him—and may miss both his policies and his reflexive support of ours. Not to mention Carla Bruni. Tant pis.