In November 2015, I wrote a column titled, “$15 Minimum Wage is Uncharted Territory,” discussing New York’s minimum wage law and speculating on its effects. Given how early we are in the process, however, we know very little currently. New York is not the first jurisdiction to attempt to address low wages legislatively, however. We’re now receiving reports from the territorial explorers in Seattle. And the news, while unsurprising, is disappointing to those who hope to help low wage workers by passing a higher minimum wage.

In November 2015, I wrote a column titled, “$15 Minimum Wage is Uncharted Territory,” discussing New York’s minimum wage law and speculating on its effects. Given how early we are in the process, however, we know very little currently. New York is not the first jurisdiction to attempt to address low wages legislatively, however. We’re now receiving reports from the territorial explorers in Seattle. And the news, while unsurprising, is disappointing to those who hope to help low wage workers by passing a higher minimum wage.

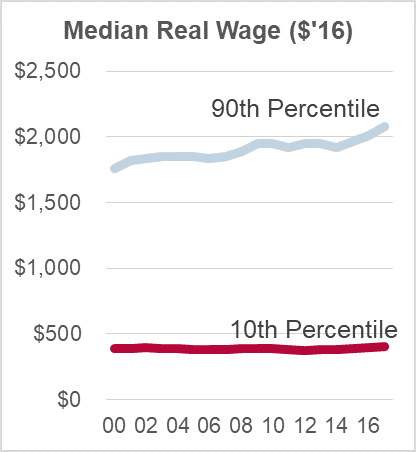

Low and stagnant incomes at the bottom of the income distribution and the growing gap between high and low wage workers are serious problems for families with low incomes and for the economy. These trends are also potentially destabilizing for society.

Low and stagnant incomes at the bottom of the income distribution and the growing gap between high and low wage workers are serious problems for families with low incomes and for the economy. These trends are also potentially destabilizing for society.

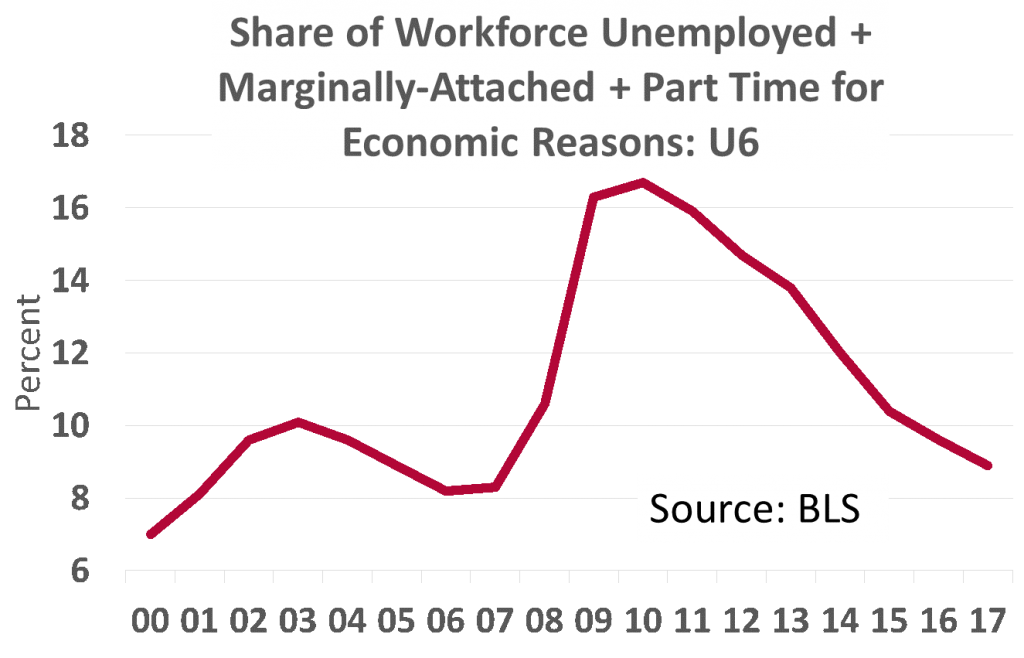

By most measures, the economy has recovered from the Great Recession and we can reasonably expect that jobs will increase and wages rise over the near future. Even the “U6” unemployment rate, which captures those on the fringes of the labor force, is approaching 2007 levels. The real median wage rate for all workers has been going up, albeit slowly, since the middle of 2014.

By most measures, the economy has recovered from the Great Recession and we can reasonably expect that jobs will increase and wages rise over the near future. Even the “U6” unemployment rate, which captures those on the fringes of the labor force, is approaching 2007 levels. The real median wage rate for all workers has been going up, albeit slowly, since the middle of 2014.

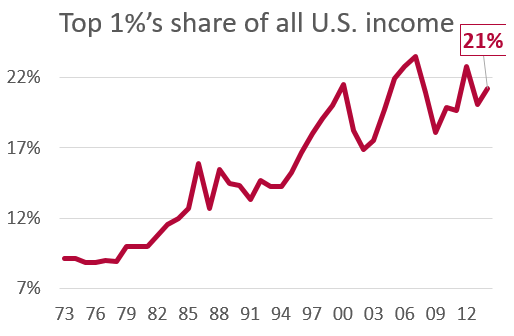

But wages going to those on the bottom of the income spectrum have been stagnant for decades, even as wages at the top have continued to rise. Well-publicized work by French economist Thomas Piketty noted that the top 1% of income earners in the United States receive 21% of all income, an income distribution reminiscent of the Roaring 20s. The top 1% received only 9% of all income as recently as 1978.

Legislators ask, “Can’t we just fix this problem?” In the spirit of “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” legislative bodies are encouraged to fix the problem with a law, typically raising the minimum wage.

Legislators ask, “Can’t we just fix this problem?” In the spirit of “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” legislative bodies are encouraged to fix the problem with a law, typically raising the minimum wage.

And that’s what we’ve done in New York. The minimum wage in New York state rose to $9.70 statewide at the end of 2016 while remaining at $7.25 nationally. NYC organizations employing more than 10 workers must pay $15 by the beginning of 2019. All NYC employers follow suit a year later. The wage Upstate tops out at $12.50 beginning in 2021.

But we must consider whether this legislative strategy will have the desired effect. On the left, we’re led to believe that a minimum wage rise will significantly improve the well-being of the poor and that employment could actually increase as a consequence. The right declares that jobs for the most disadvantaged would disappear and that the increase might trigger a recession.

Economists are nearly unanimous in observing that a minimum wage hike has both winners and losers among the groups it is intended to help. This is typical for public policy—only rarely can we make substantive changes that help all and hurt none.

This makes the finding from Seattle unsurprising to most economists. The finding is made more important by the robust foundation on which it is based.

First, the results. The University of Washington (through its schools of Public Policy and Social Work) was awarded a multimillion dollar, multiyear contract, funded by government and foundations, to study the effects of the minimum wage hike on Seattle’s workers and businesses.

The recently released report examines on the effect of the wage increases on Seattle’s entire low wage labor market, defined as jobs paying $19/hour or less, after two consecutive wage increases from $9.47/hour to as much as $11/hour on April 1, 2015, and from $11/hour to as much as $13/hour on January 1, 2016. (The range is determined by firm size.)

Quoting from the report:

“The second Seattle minimum wage increase, to as much as $13/hour on January 1, 2016, resulted in:

- a 3% increase in hourly wages for low wage employees

- a 9% reduction in hours worked at wages below $19/hour. A disemployment effect of this size would occur if, for example, a business that employed 11 low wage workers per shift in 2014 cut back to about 10 workers per shift in 2016.

- a reduction of over $100 million per year in total payroll for low-wage jobs, measured as total sum of increased wages received less wages lost due to employment reductions. Total payroll losses average about $125 per job per month.

- The findings that total payroll for low wage jobs declined rather than rose as a consequence of the 2016 minimum wage increase is at odds with most prior studies of minimum wage laws. These differences likely reflect methodological improvements made possible by Washington State’s exceptional individual-level data. When we replicate methods used in previous studies, we produce the same results as previously found. ” See https://evans.uw.edu/policy-impact/minimum-wage-study.

What makes this study distinct is the remarkably detailed data made available to the researchers by the State of Washington under a confidentiality agreement. Washington collects—and provided to the researchers—information on hours worked, only one of 4 states that collects this information. Again, from the study: “These unique data allow us to identify jobs that pay low wages and workers who earn low wages. Prior studies without hours data have had to define “low wage jobs” imperfectly (e.g. by focusing on the food service industry or teenage workers).”

This is a complex report with many implications. And they are only just getting started. The confidentiality agreement with the State of Washington will allow the researchers to cross-reference employment experience with personal characteristics, thus allowing an assessment of how the minimum wage hike affects workers in different circumstances, and, through surveys of firms and employees, other implications. The School of Social Work is leading a longitudinal analysis of a group of affected families through a series of interviews.

Low wages are a critical problem for the economy and for society. And a minimum wage is one tool that can be used to address the problem. While still preliminary, this study indicates that the ability of firms to cut hours when workers are better paid can result in lower overall income for the workers. There are opposing interpretations of the Seattle data, to be sure, but only the UW researchers had access to the detailed worker statistics. This rich dataset will help economists and policymakers refine the strategies we pursue to improve the lot of low income workers.