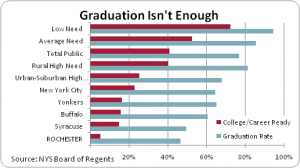

Confronted by a Regents study declaring that only 5 percent of Rochester City School District graduates are college-ready, Jean-Claude Brizard declares the findings “terrifying.”

One of Brizard’s best qualities is his persistent willingness to look the facts in the face. Too often our education leadership—the district administration and the Board of Education—has been unwilling to state the obvious. It is a natural reaction: The task is herculean. The need is desperate. The consequences of failure are tragic.

Three years into Brizard’s tenure, the results are still abysmal, as this Regents report observes so bluntly. Disappointed, some of us declare, “He has had three years and has failed.”

Perhaps poor children cannot learn. Perhaps RCSD teachers cannot teach. Perhaps the Rochester Teachers Association contract so binds superintendents that no change is possible.

I think we must reject fatalistic propositions that poverty determines a child’s future, or that the teachers are incompetent or that they are so bound up in defending their own interests that they have forgotten the needs of children.

Some charter schools (think Rochester Prep) and some traditional public schools (think School 58) demonstrate that startling success is possible. Brizard has set the wheels in motion for the kind of fundamental structural change that is required if we hope to bring a fraction of this kind of success to the entire district:

- The Rochester Curriculum begins the slow process of establishing consistent expectations across district classrooms. The assessments that accompany the new curriculum will begin the process of raising those expectations.

- The Portfolio Plan asserts that the superintendent and the Board of Education will act to close failing schools. Threat of closure is a club. It cannot be the only tool in the reform toolkit, but it is a necessary one. The new schools created under the plan must be held to even higher standards.

- District leadership is focusing a significant share of its attention on empowering principals. They are the change agents at the building level. The “autonomous schools” effort grants principals more control over staffing decisions and use of funds.

- The Charter Schools Compact, funded by the Gates Foundation, seeks to take the lessons of successful public schools living outside the direct management of the district and apply them to schools within the district.

- How teacher effectiveness is assessed and teacher development provided is in process, strengthened by reforms at the state level that are driven by Race to the Top. While institutional obstacles stand in the way of every change, here the teachers’ collective bargaining agreement looms large.

- In terms of the teachers’ agreement, make no mistake: This is a struggle over who has what power in the classroom, in the school and in the district as a whole. Understandably, the teachers want to preserve as much control as possible. That is a natural human reaction. And teachers are the closest to the students. But they also must function as part of the District’s instructional team.

- The attempt to empower principals to make effective decisions on behalf of a school is constrained by the power retained by teachers to rule their classrooms and to bid for positions based on seniority. The quid pro quo with principals is that authority comes with accountability. And the principals (also in a collective bargaining unit) aren’t always interested in the bargain.

- Further, the collective bargaining agreement’s emphasis on longevity over competence means that budget cuts will erode teacher quality, not improve it, as the district is forced to lay off teachers without any consideration of quality.

- The Rochester Teachers Association has declared negotiations to be at impasse, particularly over the issue of teacher assessment. It is time for the community to support sensible reforms that shift power back to the superintendent and Board of Education. Yes, teachers must be partners in this critical venture and must be empowered through effective school and district leadership. But some powers—the power to insulate ineffective teachers, inordinate power over teacher placement, power over instructional time must flow back to district leaders.

Yes, Brizard has had three years. Yet he leads a large and complex organization that is resistant to change. The wheels are in motion. Let’s throw grease in the gears, not sand. And let’s get behind the train and push.

Kent Gardner is president and chief economist of the Center for Governmental Research Inc.