New York State has been working to make a high school diploma meaningful for most of the past two decades, and the work continues. Since a push toward higher standards began in the mid-1990s, the state tightened graduation requirements twice: first requiring all students to pass 5 Regents exams, then increasing the minimum score to pass from 55 to 65.

New York State has been working to make a high school diploma meaningful for most of the past two decades, and the work continues. Since a push toward higher standards began in the mid-1990s, the state tightened graduation requirements twice: first requiring all students to pass 5 Regents exams, then increasing the minimum score to pass from 55 to 65.

Many feared graduation rates would plummet, but recently released data showed they’ve mostly held steady or increased. In the last five years, as the 65 minimum score was applied to more and more tests, the statewide graduation rate increased from 69% to 74%. New York City gained 8 points, rising from 53% to 61%, and the combined rate for students of the 4 next largest cities (Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse and Yonkers) also increased from 47% to 53%. Rochester’s performance remained the lowest of the five, with a graduation rate of 46% in 2011.

Many feared graduation rates would plummet, but recently released data showed they’ve mostly held steady or increased. In the last five years, as the 65 minimum score was applied to more and more tests, the statewide graduation rate increased from 69% to 74%. New York City gained 8 points, rising from 53% to 61%, and the combined rate for students of the 4 next largest cities (Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse and Yonkers) also increased from 47% to 53%. Rochester’s performance remained the lowest of the five, with a graduation rate of 46% in 2011.

At the same time, the federal government has gotten tougher about how states are to calculate graduation rates. Starting with the class of 2010, schools had to include every student in their building for even one day in their graduation cohort – the previous threshold had been 5 months. That means schools are held accountable for those students – those who moved or transferred don’t count against them, but missing students are considered dropouts.

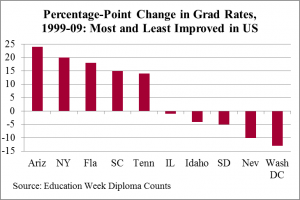

Clearly, graduation rates of 50% or even 74% aren’t high enough – non-graduates face a precarious future. But schools should be credited with graduating more students despite the tougher standards. This is confirmed by a comparison of state graduation rates by Education Week. From 1999 to 2009, New York had the second highest increase in graduation rates in the nation, gaining nearly 20 percentage points.

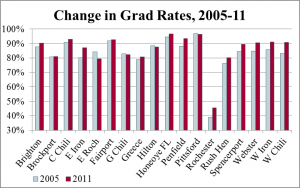

In Monroe County, every district but East Rochester either increased its graduation rate from 2005-11 or held steady. In relative terms, the biggest gainers were Wheatland Chili, Rochester and East Irondequoit.

In Monroe County, every district but East Rochester either increased its graduation rate from 2005-11 or held steady. In relative terms, the biggest gainers were Wheatland Chili, Rochester and East Irondequoit.

Simple Graduation Isn’t Enough

Yet these gains aren’t enough: not only do we need to get more students graduating, but we need to revisit the question of what a diploma is worth. Prompted in part by low college graduation rates, the state Board of Regents (our education policymakers) took a second look at its Regents exams and decided the 65 threshold wasn’t high enough to ensure post-secondary success. In addition to graduation rates, the state now reports a second benchmark of high school success: the proportion of students earning scores of at least 75 on the Regents English exam and 80 on Regents math. Far fewer students meet this standard, just 35% of the class of 2011 statewide, including 21% of New York City students, 11% of Buffalo students and 6% of Rochester students.

The state plans to change its tests to better measure college and career readiness, but the Regents acknowledge that process will take time. And they are considering other changes too, most significantly dropping one of the 5 required Regents exams (Global History and Geography, which has the highest failure rate) and allowing students to instead graduate by passing a career and technical assessment or a second math or science exam.

Social studies teachers are protesting the change, but the Regents have good reasons to consider it. The overall goal is to create multiple pathways to a diploma, including ones that lead more directly from high school to work, community college or additional technical education outside of a four-year college. The idea is persuasively argued in a 2011 Harvard Graduate School of Education report Pathways to Prosperity that our nation’s focus on “college for all” has not only been unsuccessful but is also poorly matched to the current and future job market. The economy has as many or perhaps more opportunities for technically skilled high school graduates with some post-secondary education or training than for aimless bachelor’s degree holders. In 2018, forecasters project that 36% of all jobs will require a high school diploma or less, 30% will require some post-secondary education, and 33% will require at least a bachelor’s – hardly data that supports the “college for all” mantra.

The Pathways report argues for much more vocational education in our system, closely linked to employers with lots of work-based learning opportunities, not only to better prepare students for the job market they face but also to hold their interest in school. Students who can see how learning connects to a future job in a field they find interesting get more excited about school. The changes contemplated by the Regents, while they would continue to change the graduation yardstick in ways that might be unsettling for schools, seem well worth considering.