I attended a Great Schools for All event on November 10, a discussion of the school reform efforts of Raleigh, NC. Underlying the discussion was the proposition that when a substantial share of children in a classroom are in poverty, it is nearly impossible for students to achieve at a high level. Raleigh, part of the Wake County school district, responded to poverty concentration by establishing and preserving a balance of poor and non-poor children in every school in the district. Raleigh points to trends in graduation rates and other indicators that suggest that the policy has been effective. See Hope and Despair in the American City: why there are no bad schools in Raleigh, by Gerald Grant, Professor Emeritus, Syracuse University. A book review and summary can be found here.

I attended a Great Schools for All event on November 10, a discussion of the school reform efforts of Raleigh, NC. Underlying the discussion was the proposition that when a substantial share of children in a classroom are in poverty, it is nearly impossible for students to achieve at a high level. Raleigh, part of the Wake County school district, responded to poverty concentration by establishing and preserving a balance of poor and non-poor children in every school in the district. Raleigh points to trends in graduation rates and other indicators that suggest that the policy has been effective. See Hope and Despair in the American City: why there are no bad schools in Raleigh, by Gerald Grant, Professor Emeritus, Syracuse University. A book review and summary can be found here.

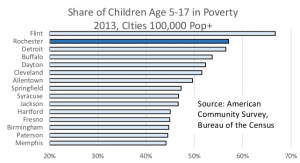

That concentrated poverty makes the school’s task more difficult is self-evident. As has been quoted by the Rochester Area Community Foundation’s recent poverty report and in other contexts, child poverty in Rochester is nearly the highest in the nation. Of cities with at least 100,000 residents, we were #2 last year, according to the Census Bureau (poor Flint, Michigan beats us handily—67% to 57%). We have very little company—only six cities are above 50%. The median is less than half our rate at 26%. Download the spreadsheet.

That concentrated poverty makes the school’s task more difficult is self-evident. As has been quoted by the Rochester Area Community Foundation’s recent poverty report and in other contexts, child poverty in Rochester is nearly the highest in the nation. Of cities with at least 100,000 residents, we were #2 last year, according to the Census Bureau (poor Flint, Michigan beats us handily—67% to 57%). We have very little company—only six cities are above 50%. The median is less than half our rate at 26%. Download the spreadsheet.

This problem isn’t new. And it is getting worse. In 1990, 37% of children were in poverty and our ranking was #15. We share this problem with Buffalo and Syracuse. Both have experienced rising child poverty over the period and are on the “top ten” list with us. Most of our fellows at the top of the list are also former industrial powerhouses—Detroit, Dayton, Cleveland, Allentown and Springfield, MA.

Poverty isn’t destiny—nor is it the lack of income alone that explains the challenge. Rather, it is the constellation of challenges that are associated with poverty—from malnutrition to social dysfunction and racism. Thus while a child in poverty can learn, a school filled with children in poverty will likely be overwhelmed by the problems they bring to school with them.

City schools are caught up in a vicious cycle. Poor test scores spur middle class families to flee to the suburbs when children reach school age, leaving a more impoverished population behind.

I suspect that the district’s “school choice” policy is partly to blame for the increasing concentration of poverty. We can agree that it is unfair to have good schools in prosperous neighborhoods and bad schools in poor ones. District-wide school choice was intended to grant all families equal access to the better schools and encourage the less popular schools to improve. But it appears to have had the unintended consequence of hastening the departure of middle-class families who cannot guarantee a good school for their children by selection of a neighborhood. Choice has leveled the playing field—but by reducing the number of good schools, rather than spurring widespread improvement

Few schools have retained a strong neighborhood connection. Improving parental engagement—another factor known to be correlated with achievement—is far more difficult when parents live all over the city.

In a way, we still have “neighborhood” schools, but the neighborhoods are the 19 county school districts. Those who can afford to locate in a better district do so.

So here’s our problem: We know that concentrated poverty makes Rochester’s challenge nearly intractable. And one solution would be to share the burden of poverty more evenly.

Roughly half of the children in poverty in Monroe County are in the city. Distributing poverty across the county’s schools would be a massive undertaking—and massively unpopular outside Rochester. The potential social benefits of racial and ethnic mixing and the economic benefits of a functional, unified school system are real. But to homeowners and parents in well-regarded school districts, the perceived risk would loom larger in the minds of voters and could promote a backlash at the polls.

This leaves us with fewer options. Reducing the concentration of poverty doesn’t take away the problems associated with poverty, although it makes the job of the school more tractable. The problem is systemic; so must the solution be.