We stand watch at Obamacare’s bedside, filled with uncertainty about the timing of its demise and what will follow. There are good deaths and bad deaths—good ones are peaceful and offer time for reflection and fond farewells. Bad deaths are filled with misery and leave behind discord, estrangement and confusion.

We stand watch at Obamacare’s bedside, filled with uncertainty about the timing of its demise and what will follow. There are good deaths and bad deaths—good ones are peaceful and offer time for reflection and fond farewells. Bad deaths are filled with misery and leave behind discord, estrangement and confusion.

Born of compromise

Although the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed without Republican support, it did not emerge full grown from the head of Obama. Unlike the Clinton Health Care Reform, the Obama Administration consulted with and received the support (mostly) of the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Society, America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), Consumers Union, and many other interested parties. The Obama Administration did not want to resurrect the AHIP-funded Harry & Louise ads that doomed the 1993 Clinton plan. Born of compromise, ACA was a frail child.

Each of the interested parties got something in exchange for their political support. AHIP won the personal and employer coverage mandate and dodged the “Medicare for All” public option. AHA, courtesy of the “out of pocket maximum,” hoped for fewer bankruptcy-driven write-offs. PhRMA escaped negotiated drug prices. AMA’s support bought a long list of free preventative services, like annual physicals and screenings. Consumers advocates won community rating coupled with an end to “pre-existing condition” exclusions.

Rejecting the “single payer” models of the United Kingdom and Canada, the ACA retained private insurance and provider markets, imitating the health care systems of many of our trading partners, e.g. Germany, France, Japan and Switzerland. While private, the payers and providers in these countries are subject to comprehensive price regulation.

Obama’s Goal: Increase Health Insurance Coverage

The deal cut with interest groups secured the top priority of the Obama Administration and its allies in Congress, an expansion of health care coverage. Before passage of the ACA, two groups found health care insurance inaccessible—the very poor in states with limited Medicaid coverage and the near poor without employer coverage.

The number of uninsured fell from about 49 million in 2010 to 29 million in 2017. The Commonwealth Fund’s tracking survey reports that 14% of working age Americans were without health insurance at the end of 2017, down from 20% in July-Sept 2013.

But Who Pays the Bill?

The 64 trillion dollar question: How would the ACA pay for the simultaneous improvement and expansion of coverage?

Part of the cost would be paid by new taxes. President Obama widely claimed that the law “would not add one penny to the deficit.” His careful wording only meant that new revenue would equal new cost, not that the plan would not cost more.

The second source of revenue is other rate payers.

Consider the “out of pocket maximum:” It has been widely claimed (and debated) that unpaid medical bills were the single most common cause of personal bankruptcy prior to the ACA. The out-of-pocket maximum, currently $7,350 for an individual and $14,700 for a family, makes this much less likely. Take coronary angioplasty—one of the ten most common medical procedures in America. The average cost in the U.S. is over $35,000 ($47,000 in NYS), according to Guroo.com, a site that gathers and reports health care claims data. The difference ($28,000 for an individual) is “paid by the insurance company”—which is the rest of us. Consumer Reports observes that personal bankruptcies dropped by half since the ACA was fully implemented (although, again, the ACA connection is disputed).

Mandating preventative services also adds cost. We would like to believe that “a stitch in time saves nine.” But that is not what the research tells us. Prevention improves quality of life but does not actually reduce overall spending. “The insurance company”—the rest of us, remember—is obliged to pay the difference.

And, of course, insurance companies may no longer keep rates down by excluding expensive patients or by charging them more. They cannot say, “You’ve had cancer? Sorry, try another company.” By bringing individuals with costly conditions back into the insured “pool” and charging them no more than people of the same age without the risky history, the sum “paid by the insurance company”—which is the rest of us—simply had to rise.

Premiums Rise for Many

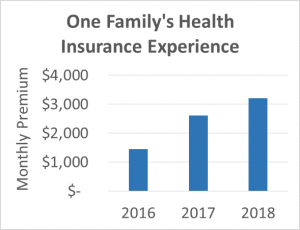

A case study offers insight into the cost impact for ratepayers without costly conditions. A cousin of my wife’s is self-employed and was happily enrolled in an ACA marketplace plan in 2016. Changes in his Pennsylvania market spurred an 80% increase in his monthly premium, which includes his wife and two young children. Instead of paying the $2,600/month premium, he sought out a religiously-based “medical cost sharing” arrangement. For 2018, the price of his former plan went up again to $3,200 per month. The sharing plan costs $750 per month. He has no guarantee of coverage—this is not insurance—although the fund has been paying claims regularly for 20 years. Pre-existing conditions are excluded. The nonprofit also limits the pool by not enrolling smokers or individuals who participate in a list of other “risky behaviors.” In other words, this sharing plan looks a lot like many health insurance plans made illegal by Obamacare. Competitive market forces also play a role in this pricing comparison, of course, but that is another post.

A case study offers insight into the cost impact for ratepayers without costly conditions. A cousin of my wife’s is self-employed and was happily enrolled in an ACA marketplace plan in 2016. Changes in his Pennsylvania market spurred an 80% increase in his monthly premium, which includes his wife and two young children. Instead of paying the $2,600/month premium, he sought out a religiously-based “medical cost sharing” arrangement. For 2018, the price of his former plan went up again to $3,200 per month. The sharing plan costs $750 per month. He has no guarantee of coverage—this is not insurance—although the fund has been paying claims regularly for 20 years. Pre-existing conditions are excluded. The nonprofit also limits the pool by not enrolling smokers or individuals who participate in a list of other “risky behaviors.” In other words, this sharing plan looks a lot like many health insurance plans made illegal by Obamacare. Competitive market forces also play a role in this pricing comparison, of course, but that is another post.

The official statistics confirm the anecdote directionally, although rate growth varies dramatically by individual market. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reports that while inflation-adjusted health insurance cost per enrollee rose a modest 12% overall from 2010-2016, the cost of insurance for “direct purchase” enrollees (like my wife’s cousin) rose 63%. And that’s just the figure to 2016.

ACA “marketplace” plans, a subset of the direct purchase plans, also saw premiums soar. “Silver” plan premiums rose 64% from 2015 to 2018, 38% from 2017-2018 alone.

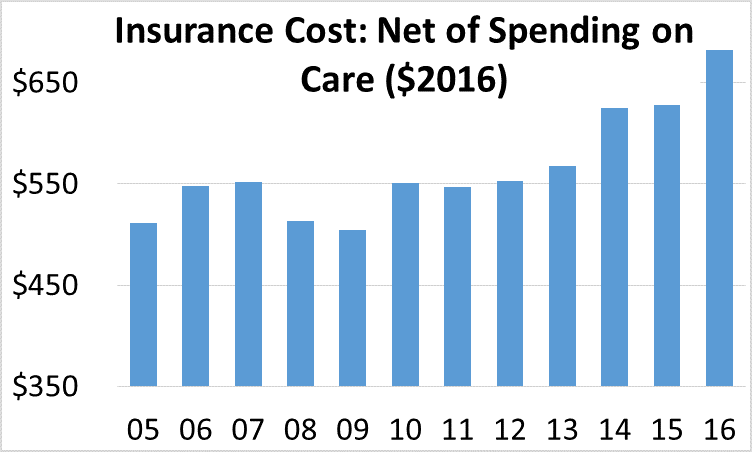

CMS also reports that the inflation-adjusted “net cost” of health insurance—defined as premiums less the cost of services received—rose by 20%, adjusted for inflation (Table 2 National Health Expenditures; Aggregate, Annual Percent Change, Percent Distribution and Per Capita Amounts, by Type of Expenditure: Selected Calendar Years 1960-2016). This tells us that while the extra spending bought more benefits, the cost of coverage rose more.

CMS also reports that the inflation-adjusted “net cost” of health insurance—defined as premiums less the cost of services received—rose by 20%, adjusted for inflation (Table 2 National Health Expenditures; Aggregate, Annual Percent Change, Percent Distribution and Per Capita Amounts, by Type of Expenditure: Selected Calendar Years 1960-2016). This tells us that while the extra spending bought more benefits, the cost of coverage rose more.

Mergers Reduce Competition

The ACA also spurred a flurry of mergers across the health sector and has included hospitals, physician practices and insurers. The consultancy Kaufman Hall reports that the number of 2017 mergers was the highest since it began keeping track in 2000. The average annual number of mergers in the seven years since passage of the Affordable Care Act (101) is a 71% increase over the number recorded for the seven years ending in 2010 (59). Competition cannot solve every problem but the lack of it typically drives up prices.

Not the Plan

These cost impacts are driven by the ACA design and were, to a degree, anticipated. The bill’s architects hoped that by adding reasonably-healthy and previously-uninsured individuals to the pool (through the individual and business mandates) and by ramping up cost reduction initiatives, the increase in premiums would be mitigated. Where unanticipated cost increases threatened the viability of insurers (and higher premiums as a buffer), the federal government was to provide funding to bridge the gap, playing a kind of “reinsurance” role.

While the arithmetic was tenuous under continued Democratic control, Republican opposition removed these mitigating influences—the individual mandate was rendered toothless and the “reinsurance” payments to insurers were ended.

We are left with a health care system that is far better for some and far worse for others. Courtesy of state opposition to Medicaid expansion, many below the poverty line lack any coverage at all while neighbors who are “near poor” qualify for robust Marketplace subsidies.

Low to middle income individuals and families who qualify for a small or zero subsidy are stuck with plans offering high deductibles and high premiums, both a reflection of the higher cost of ACA’s improved coverage and access. Without an effective coverage mandate and faced with high deductibles, a decision to forgo insurance is tempting to many and may be economically rational for those who have little to lose from bankruptcy.

What about Rochester/Finger Lakes?

New York’s State Insurance Law already embraced much of what is in the Affordable Care Act. New York required individual market insurers to accept all applicants regardless of pre-existing conditions and charge the same premiums regardless of an applicant’s age in 1992. As a result, the transition to Obamacare was less significant in NYS.

Yet prior law in NYS did not require that individuals purchase health insurance. The cost of individual plans was prohibitive as a result and few enrolled. With ACA’s individual mandate de-fanged by Congress and the White House, NYS health care may be a re-run of “Back to the Future” (but without the cool DeLorean).

Rochester has also been insulated from some of the market chaos by the delicate bi-lateral power sharing between insurers (Excellus & MVP) and hospital systems (UR Medicine and Rochester Regional).

What’s next?

In a subsequent post we will explore what might replace Obamacare. Activists on the left are supporting something like Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All.” Conservatives seek to restore “bare bones” health insurance, turning the clock back to an earlier era. Individual states have been exploring how they might chart a different course, possibly creating a single state “single payer” model.

The status quo ought to be intolerable—yet the balance of power between left and right (and among the left & among the right) seems to place substantive reform beyond reach. At this writing, the consensus forecast has Democrats winning the House of Representatives and the Republicans holding the Senate, a recipe for further gridlock.