As you’ve read elsewhere and heard from politicians ad nauseum, the middle class in America is shrinking. The consequences for society are significant and should not be underestimated. Let’s first review the facts, as reported recently by the Pew Research Center, then explore the reasons and possible consequences.

As you’ve read elsewhere and heard from politicians ad nauseum, the middle class in America is shrinking. The consequences for society are significant and should not be underestimated. Let’s first review the facts, as reported recently by the Pew Research Center, then explore the reasons and possible consequences.

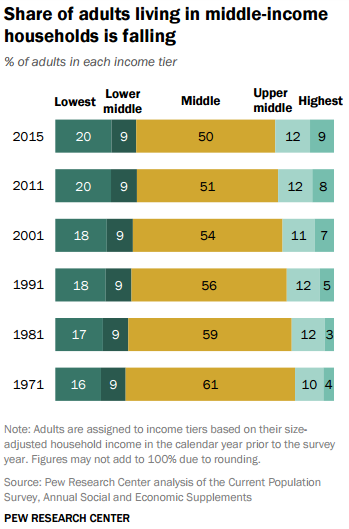

Pew observes that the number of adults considered “middle class”—about 121 million—is now equal to the number both above and below them by income. Look back to 1971 and you’ll see a quite different distribution—instead of half, 61% of Americans were in the middle class.

Pew observes that the number of adults considered “middle class”—about 121 million—is now equal to the number both above and below them by income. Look back to 1971 and you’ll see a quite different distribution—instead of half, 61% of Americans were in the middle class.

Pause for definition: Pew considers “middle income” as two-thirds to twice the median household income. In 2014, the middle extended from $34,186 to $102,560 for a family of two. A family of four with income between $48,347 and $145,041 is “middle income.” You get the idea.

Middle income families today also take home a smaller share of total income. In 1971, with 61% of the adults, the middle class took home 62% of total income. Now 50% of adults, the middle tier takes home 43% of total income.

The winners, of course, are the upper income households. About 29% of adults live in the bottom tier today, a bit more than the 25% in 1971. The ranks of the upper income group grew substantially, however, from 14% of the total then to 21% today.

Oh, my. So many numbers. You really ought to look up the Pew report.

Let me pull out a few more stats before I go on. By the numbers, every income class is better off today than in 1971. Adjusted for inflation and scaled to a three person household, the median income of the lower income tier rose 28% from 1970 to 2014 to $24,074. The middle income median rose 34% to $73,392. And the winners, as usual, are the upper income group whose median income rose 47% to $174,625.

Ah, but poverty is really not defined in absolute terms, but relative to others. By that standard, middle and lower income Americans feel poorer, despite inflation-adjusted gains. And all three groups have lost ground recently (largely due to the Great Recession). Median income in the upper and middle income tiers dropped 3% and 4% respectively from 2000. The lowest income tier lost 9%.

Ah, but poverty is really not defined in absolute terms, but relative to others. By that standard, middle and lower income Americans feel poorer, despite inflation-adjusted gains. And all three groups have lost ground recently (largely due to the Great Recession). Median income in the upper and middle income tiers dropped 3% and 4% respectively from 2000. The lowest income tier lost 9%.

Wealth variation across the tiers is even more striking. In 1983 (the earliest year reported in the Pew study), the median net worth of the upper class was just over three times that of the middle class. Although net worth in the middle rose from $96,000 in 1983 to $161,000 in 2007, the Great Recession blew a big hole in the middle income nest egg, driving net worth back down to $98,000 by 2013. While the upper income tier also took a hit in the recession, its median net worth sat at $650,000 in 2013, nearly seven times that of the middle income adult.

The bottom fared the worst. Median net worth of the lowest income tier actually fell from $11,500 in 1983 to $9,500 in 2013.

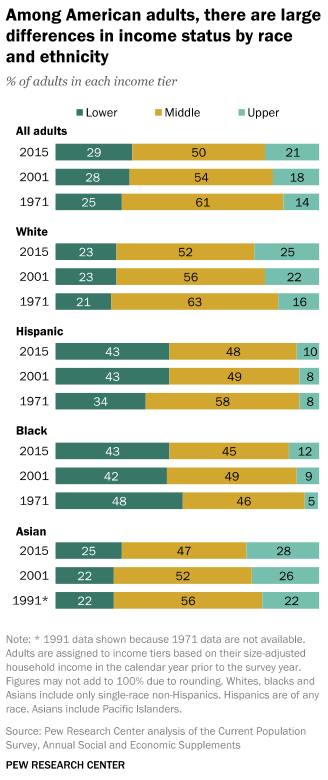

Finally, Pew explores these income trends by race and ethnicity, demonstrating that the gaps remain obscenely large, although black adults gained more ground than any other demographic group except the elderly and those classified as “married, no children.”

Enough already. What happened? There is no shortage of reasons.

- Sheer competition for low skill work is consequential. The industrialization of China and its entry into world markets, the fall of the Soviet Union and its new-found openness to capitalism, rising educational standards in Asia, and many other trends have made it hard for the middle class to grow and prosper.

- Global competition, both at the firm and worker levels, partially explains why unions have lost power.

- Telecommunications, improved logistics, the Internet and improved transportation have made it possible for firms to deliver goods and services worldwide. These changes have created a “knowledge economy” that places a premium on education. Pew tells us that adults with only a high school education lost more ground than any other group.

There are no easy lessons here. For reasons too complex to discuss here, closing our borders to global trade would make us worse off, not better off. The march of technology has brought much good. Few of us wish to emulate the Luddites, smashing smartphones and sabotaging the Internet. We do need to find better ways to protect the most vulnerable and improve their ability to compete. Not only is increasing inequality unfair on its face, I fear that social stability of our nation is at risk.