“Who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Asked of Jesus by the religious authorities of the day, this question haunts many conversations about social welfare and health policy. Self-reliance—that people should “get what they earn”—is embedded in America’s cultural mythology. In some subtle way, people in poor health must be responsible for their condition and simply have to pay when illness strikes.

“Who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Asked of Jesus by the religious authorities of the day, this question haunts many conversations about social welfare and health policy. Self-reliance—that people should “get what they earn”—is embedded in America’s cultural mythology. In some subtle way, people in poor health must be responsible for their condition and simply have to pay when illness strikes.

This is the moral question underlying health policy: Who should bear the cost of caring for the sick? That we are neither wholly blameless or nor wholly guilty for the state of our health is the Gordian knot we labor in vain to untie. We know that smoking often causes lung cancer and obesity can trigger diabetes. But not all lung cancer comes from smoking and diabetes has other triggers. We’re not willing to deny care to victims of either disease. We admire self-reliance but also sense the injustice in “blaming the victim” for diseases and conditions that have no known link to personal decisions (and some that do). As the Republican Congress and the Trump Administration seek to unwind Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA), this “who pays?” question takes center stage.

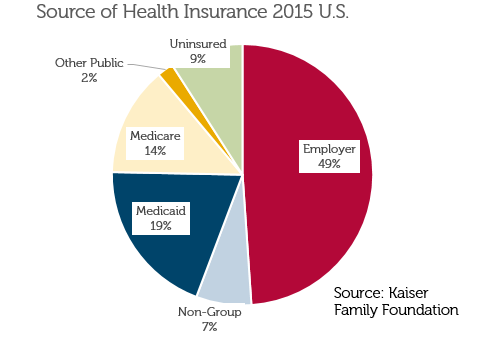

Where do we get health coverage?

About half of us get covered through our employers (29% from “self-funded” plans and 20% from insurance purchased by employers); 14% from Medicare, 19% from Medicaid and 7% from nongroup insurance—you or me buying directly from a health insurer. About 9% have no insurance coverage at all, down from about 17% before the ACA.

About half of us get covered through our employers (29% from “self-funded” plans and 20% from insurance purchased by employers); 14% from Medicare, 19% from Medicaid and 7% from nongroup insurance—you or me buying directly from a health insurer. About 9% have no insurance coverage at all, down from about 17% before the ACA.

Changes for everyone

The Coverage Mandate in Obamacare forces our healthy selves to buy insurance today against the cost of caring for our unhealthy selves tomorrow. Frankly, it isn’t “insurance” if we buy it at the moment illness strikes. The coverage mandate also has a “redistributive” element: The healthy are made to share the burdens of others less fortunate. Employers of more than 50 are also required to offer insurance, which wasn’t true before the law.

Community Rating under the ACA says that health insurance premiums must be the same for everyone in a market who are the same age and sex, regardless of health status. And the law also limits differences by age—a sixty-something like me can only be charged 3 times as much as a twenty-something. Left unregulated, health insurers would charge each of us our expected cost—just like car insurance where teens and the accident prone pay more.

If health insurance were priced like car insurance, the old and the sick would be out of luck. That’s where Guaranteed Issue comes in: This is the wonky term meaning that we can’t be denied insurance if we’re sick—a pre-existing condition can’t be the basis for turning us down.

A major health calamity can be ruinously expensive, pushing some into bankruptcy. To address this the ACA prohibits annual or lifetime limits on health insurance payouts. It goes one step further by imposing annual “out of pocket” maximums ($7,150/$14,300 for single/family plans currently). By protecting some of us from ruinous bills, all of us have to pay a bit more.

Finally, the ACA rolled out new rules on what a plan had to cover. Every plan had to cover 60% of the expected cost of care and had to include—at no cost—a fixed set of preventative services. If an ounce of prevention is really worth a pound of cure, this ought to reduce total cost over time. That contraception was included on the list was a flash point for some, prompting legal challenges that led to the Supreme Court.

Who bears the burden when illness strikes?

The coverage mandate, community rating, guaranteed issue & the out-of-pocket maximum have shifted the burden of major illness from the individual to the group, forcing us to bear more of one another’s burdens than before. Perhaps it isn’t fair, but neither is cystic fibrosis or pancreatic cancer.

What changes under the Republican plan?

The mandate is dropped in the Republican plan that passed the House of Representatives. This eliminates the cost of insurance for individuals who didn’t want to buy it in the first place. But insurance for those who DO buy will cost more as the pool will be less healthy, thus more expensive. For some of us, this means that our future selves will pay more because our present selves paid less—maybe that will balance out. Maybe not. Employers are also off the hook.

Community rating stays for those who buy insurance but with a couple of twists. You’ll pay the same as others in your market and age group, but sixty somethings can be charged 5 times as much as the twenty somethings instead of 3 times. This change is offset by a new tax credit that rises with age (with a phase out for individuals/families earning more than $75k/$150k). And straight “community rating” only applies if you stay insured. If you are uninsured for 63 days or more, you’ll have to pay 30% more for a year when you sign up again. That isn’t a big penalty—staying uninsured until you get sick will be appealing for many, again driving up rates for buyers.

The plan allows states to opt out of guaranteed issue/community rating/essential health benefits as long as they provide another way for individuals with high cost to get covered, probably through “high risk pools.” This can work—instead of the burden of these high cost individuals being borne by all buyers of health insurance (as everyone pays higher premiums), the funding for the high risk pools comes from taxpayers. And the plan provides federal tax dollars to the states to fund these pools. Opponents point out that high risk pools have often been seriously underfunded, thus leaving a large share of the burden of significant illness on the individual or family. And current rules would allow employer plans to select the rules of any state in which they do business. Again, who bears the burden of high cost care?

Let’s summarize: The ACA “beefed up” health insurance for everyone—the annual out-of-pocket maximum, no annual or lifetime limits, free preventive care, and guaranteed issue for people with pre-existing conditions made health insurance more expensive for people who once had “less beefy” coverage. By requiring that we all buy insurance and forcing health insurers to charge all within the same age, gender & market the same, the ACA spread the cost of health care over more people. That helped some and hurt others—the younger and healthier pay more and the older and sicker pay less.

The Republican plan allows people—presumably healthier people—to leave the “risk pool” and not buy insurance, which will likely increase rates for those who remain. States have the option of rolling back the ACA even further, provided that there’s a way for people who would find coverage unaffordable to get insurance another way.

Next week we’ll explore how both plans address the needs of low-income individuals and families.